An investment firm overseeing $172 billion in assets warns the AI mania now looks like late-stage internet frenzy, only bigger, with spending outrunning real revenue and valuations stretched across the leaders.

In a report, the Florida-based GQG Partners says the setup risks a painful comedown, even if the technology ultimately delivers consumer benefits.

The firm points to dotcom bubble-era spending patterns, retail speculation, and multiples that already resemble 1999, not the earlier innings of a tech boom.

“Bulls will surely argue we are in 1995, not 1999—suggesting more upside ahead—but we disagree for two key reasons. First, retail mania. The resurgence of meme stocks, zero-dated options, and levered ETFs mirrors the late-stage froth of 2021, which signaled the end of the last bull run.

Second, valuations… On a trailing 12-month basis, the S&P technology subset’s price-to-sales ratio is 10x compared to 4x going into 1999, while its price-to-earnings ratio is 42x versus 46x back then. Moreover, earnings growth tells a sobering tale: at the height of the late 1990s boom, broader market growth was on the order of 18% per annum in the five years leading into 1999. Today, that figure sits closer to 10% despite valuations remaining lofty.”

On top of fundamentals, GQG warns that the revenue generated by AI natives is just a fraction of the projected CapEx (capital expenditures) over the next few years.

“We believe that a similar scenario could unfold with Al over the longer run, but in the short and medium term, the signs are questionable. ChatGPT launched nearly three years ago, yet revenues for the ‘Al Natives,’ estimated to be less than $20 billion today, still pales relative to the approximately $7 trillion data center CapEx expected by 2030.”

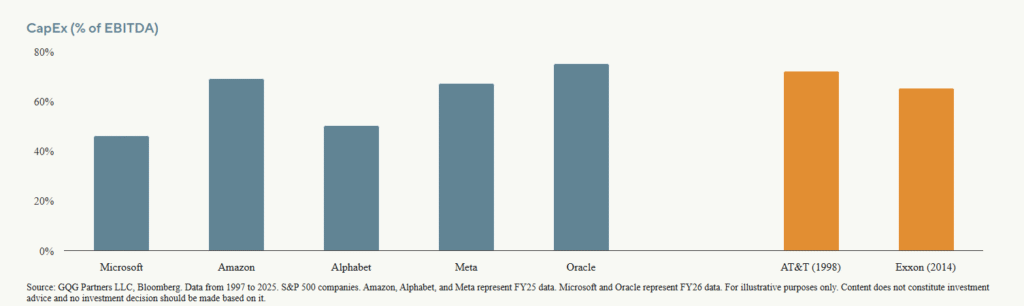

Looking closer at AI firms’ CapEx, GQG notes that the figure is already hovering close to levels that marked the height of two bubbles.

“Big tech CapEx as percentage of EBITDA is now running at 50%-70%, which is similar to AT&T’s 72% at the peak of the 2000 telecom bubble and Exxon’s 65% at the peak of the 2014 energy bubble. Historically, companies experiencing higher capital intensity tend to be structurally poor investments. In other words, AI CapEx has already caught up to prior bubble levels, even after adjusting for big tech’s initial high margins.”

GQG ends its report with an ominous question.

“At GQG, we rarely turn cautious purely based on rich valuations. However, the trifecta of rich valuations, increasing macro risk, and—perhaps most importantly—deteriorating company fundamentals is very dangerous…

So, the question for investors becomes: how much of your retirement would you bet on the AI bubble?”

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed at CapitalAI Daily are not investment advice. Investors should do their own due diligence before making any decisions involving securities, cryptocurrencies, or digital assets. Your transfers and trades are at your own risk, and any losses you may incur are your responsibility. CapitalAI Daily does not recommend the buying or selling of any assets, nor is CapitalAI Daily an investment advisor. See our Editorial Standards and Terms of Use.